The Wise King by Simon R. Doubleday

Author:Simon R. Doubleday

Language: ara, eng, fra

Format: epub

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2015-10-14T16:05:26+00:00

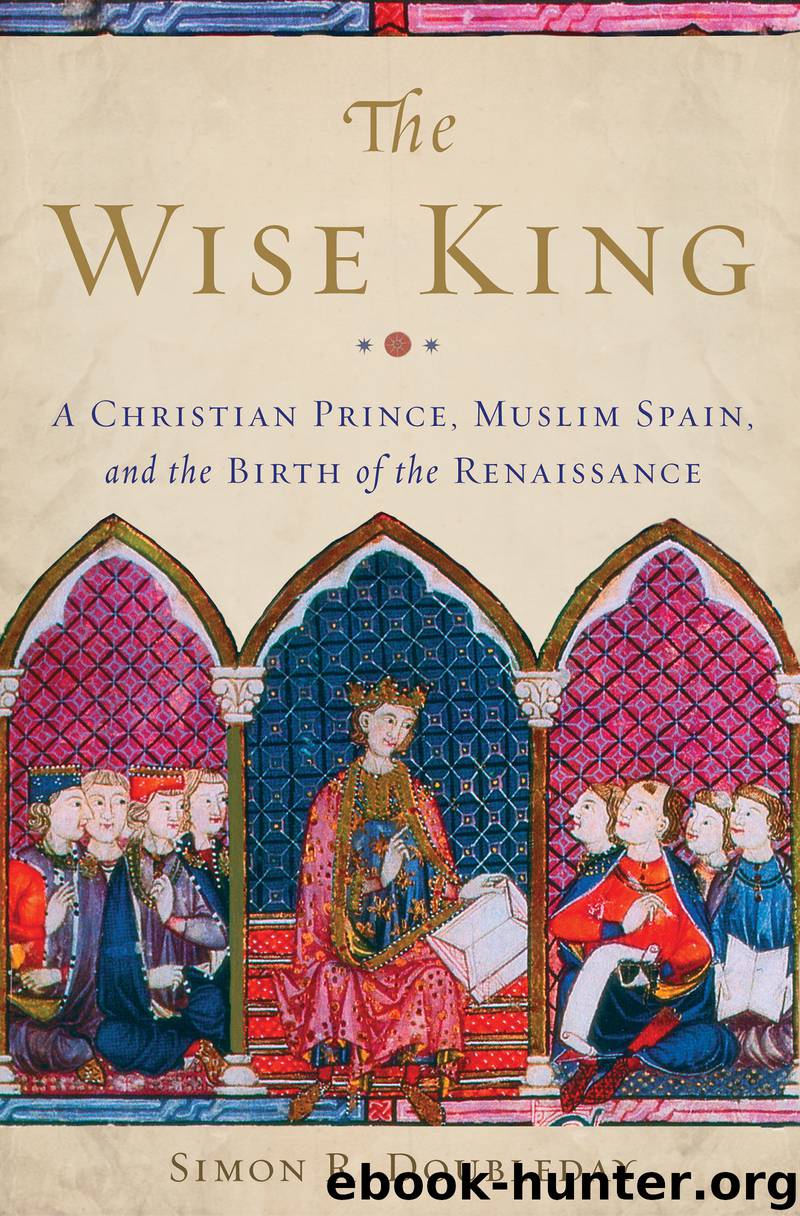

A child is miraculously unharmed after falling from a rooftop: Cantigas de Santa María, no. 282, Códice de Florencia (Florentine Codex), Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Ms. B.R.20. Reproduced courtesy of Archivo Oronoz.

It is usually difficult to determine the author of individual songs. But one cantiga revolving around the tragic death of a small child was likely composed by Alfonso himself. “I shall tell a miracle which happened in Tudia and shall put it with the others which fill a great book,” he declares at the beginning of song 347; “I made a new song about it with music of my own and no one else’s.” There is also a happy ending in the case of another deeply personal song in Alfonso’s “great book,” which tells of the nearly fatal illness of Alfonso’s own father, Fernando. He “could not sleep at all nor eat the slightest thing, and many large worms came out of him, for death had already conquered his life without much struggle.” He was miraculously healed after his mother took him on pilgrimage to Oña, becoming stronger and healthier than ever before.

“Is there anything more precious than a son, especially an only son, into whom we would pour, not only all our riches but also, if it were possible, our very life?” the sixteenth-century humanist Erasmus later asked. The young prince Fernando de la Cerda was not Alfonso’s only son—Sancho, Pedro, Juan, and Jaime were all children or adolescents in the early 1270s—but since he was the eldest and heir to the throne, the king naturally poured his soul into raising him. It is easy to imagine him showering his son with toys like those we find in late-thirteenth-century England: metal toy soldiers or something like the little toy castle made for his English namesake, Prince Alphonso, a son of Edward I, in 1279. He surely introduced the infante Fernando to the intricacies of chess or the excitement of hunting. As his son grew from infancy into childhood, he would also have taken a sharp interest in the boy’s education. Given the tradition of works written by fathers for their sons in medieval Europe—among them Walter of Henley’s Treatise on Husbandry (in the thirteenth century) and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Astrolabe (in the fourteenth)—as well as Alfonso’s own intellectual sharpness, he probably gave some informal instruction to Fernando, perhaps in history, medicine, or astronomy, as well as in rulership. He would have understood this responsibility as an extension of his fatherly affection, actively helping to choose a good tutor to complement his own lessons. It is likely that Fernando’s tutor was Jofré de Loaysa, once Queen Yolant’s tutor, suggesting that both parents may well have made the decision.

There is no doubt that medieval fathers could be authoritarian; we should not oversentimentalize childhood in this period. In his message to Fernando in 1273, the king’s tone had been kind but firm. Hierarchy within the family is as natural and unquestioned as strength of affection. In late medieval culture, this presumption shaped all written communications between fathers and sons.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Military | Political |

| Presidents & Heads of State | Religious |

| Rich & Famous | Royalty |

| Social Activists |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37781)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23069)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18564)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13306)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12012)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8360)

Educated by Tara Westover(8043)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7464)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5827)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5626)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5269)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5139)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5085)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4946)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4802)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4345)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4092)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3955)